Not long ago, reaching Antarctica required a lengthy voyage by ship from countries in the Southern Hemisphere, such as Australia, South Africa, or Chile. These trips were typically limited to the summer months when the ice was less hazardous, and the relatively warmer weather and extended daylight hours reduced logistical difficulties.

However, the situation has changed with larger jet aircraft now able to land on Antarctica's unique blue ice runways. This development has significantly improved connectivity for the scientists and supplies traveling to and from over 30 national research stations. It has also opened up the continent to more adventurous tourists seeking to explore one of the last untouched wildernesses. But what does it take to operate an ice airport in Antarctica?

Widebodies to the White Continent

The first wheeled aircraft to land in Antarctica was a Douglas DC-4 on a blue-ice runway at Patriot Hills in 1987. This successful operation led to rapid expansion, accommodating planes like the Douglas DC-6, Lockheed C-130 Hercules, and Ilyushin Il-76.

Commercial airliners eventually began operating in Antarctica, starting with the Australian Antarctic Division using Airbus A319s in 2007 to fly to the blue ice airfields at the Australian base Wilkins and the US base McMurdo. In 2022, Smartwings operated the first Boeing 737 MAX service to the Troll airfield.

More notably, various widebody aircraft have made significant journeys to Antarctica:

- Titan Airways landed the first Boeing 767 in Antarctica in 2019 at Novolazarevskaya, a Russian base.

- Icelandair has made several flights to the Troll Airfield since 2021 using Boeing 767 aircraft.

- Hi Fly has operated multiple trips to Wolf’s Fang Runway from 2021 to 2023 with an Airbus A340-300, the largest passenger aircraft to land on the continent.

- Norse Atlantic brought a Boeing 787-9 to Troll Airfield in 2023, transporting scientists and supplies to the Troll research station.

These operations require meticulous planning and specialized runways. The blue ice airfields at Wolf’s Fang and Troll are particularly notable for widebody operations.

Wolf’s Fang and Troll

Wolf’s Fang Runway, operated by White Desert, is a private airfield in Queen Maud Land, beneath the iconic Wolf’s Jaw mountain range. It holds the record for the largest passenger aircraft landing with a Hi Fly A340-300.

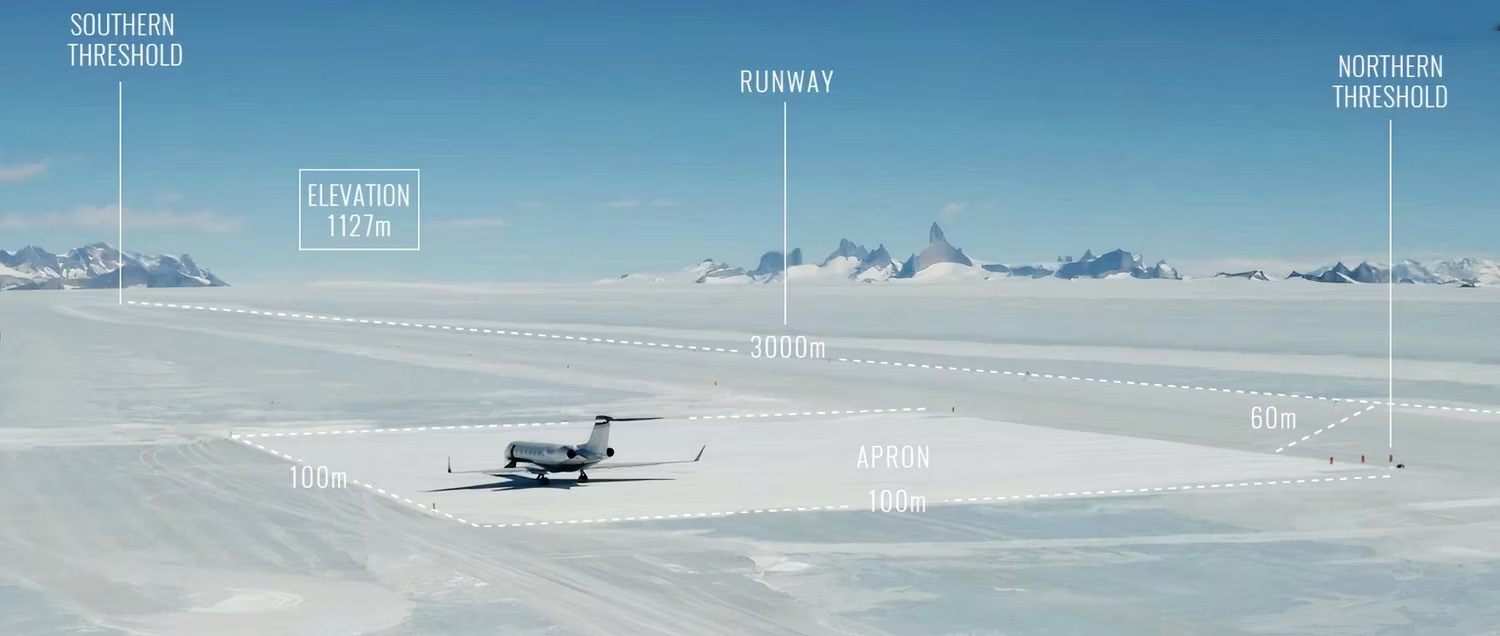

Troll Airfield, also in Queen Maud Land, is operated by the Norwegian Polar Institute. Opened in 2005, it has a 3,300-meter long and 100-meter wide runway carved into the blue ice. It regularly receives flights from Cape Town International Airport (CPT).

Constructing a Blue Ice Runway

Building these runways requires careful planning. Surveyors first identify a flat section of ice at least 3,000 meters long. At Wolf’s Fang, another key consideration was aligning with the prevailing winds for efficiency.

Construction is a lengthy process. At Troll, it took two years and involved using a laser cutter to level the blue ice. Snow groomers then carve thin grooves into the ice to provide traction for wheeled aircraft.

Maintaining the Runway

Maintaining the runway is equally challenging. During winter, the runway is covered with snow for protection. In the summer, snow blowers remove the snow up to 10 meters from the runway edges, a process that can take up to two weeks. After each flight, it takes about 12 hours to clear the airstrip of snow. The runway is closely inspected for any damage, and flights are typically suspended for 4-6 weeks in December and January due to the partial melting of the ice during mid-summer.

Other Support Services

The airfields at Wolf’s Fang and Troll offer a variety of essential support services, akin to those at conventional airports. These services include firefighting equipment and emergency medical facilities. Both airfields have on-the-ground weather teams, bolstered by weather stations across the continent, and manage communications through redundant satellite connections.

One of the most significant challenges of operating an ice airport is fuel management. Smaller aircraft, such as the Gulfstream used to transport tourists to Wolf’s Fang, need to be refueled on-site. Aviation fuel is shipped to Wolf’s Fang and Troll in 200-liter barrels aboard re-supply ships that dock at the ice shelf's edge. From there, tracked vehicles transport the fuel across hundreds of miles of the ice shelf to the airfields, where a 16,000-liter pressure fueling tank is used to refuel the aircraft.

A Widebody Future?

This is one of the key reasons why wide-body aircraft are becoming increasingly popular for Antarctic missions. They can transport a large number of passengers and cargo in just a 5-hour journey from Cape Town. Moreover, aircraft like the Boeing 787 or Airbus A340 can carry enough fuel for a round trip to Wolf’s Fang or Troll without needing to refuel.

This development is likely to spark new debates. Similar to how the Boeing 747 made transatlantic travel accessible to many, advances in modern airliners and blue ice runway management could potentially open Antarctica to a larger number of adventurous tourists. We must decide whether we want commercial wide-body aircraft to become more common in Antarctic travel, and if so, how to regulate their operations to protect this pristine environment.